Compulsory licensing: The debate continues

26 October 2012 | Analysis | By BioSpectrum Bureau

Compulsory licensing: The debate continues

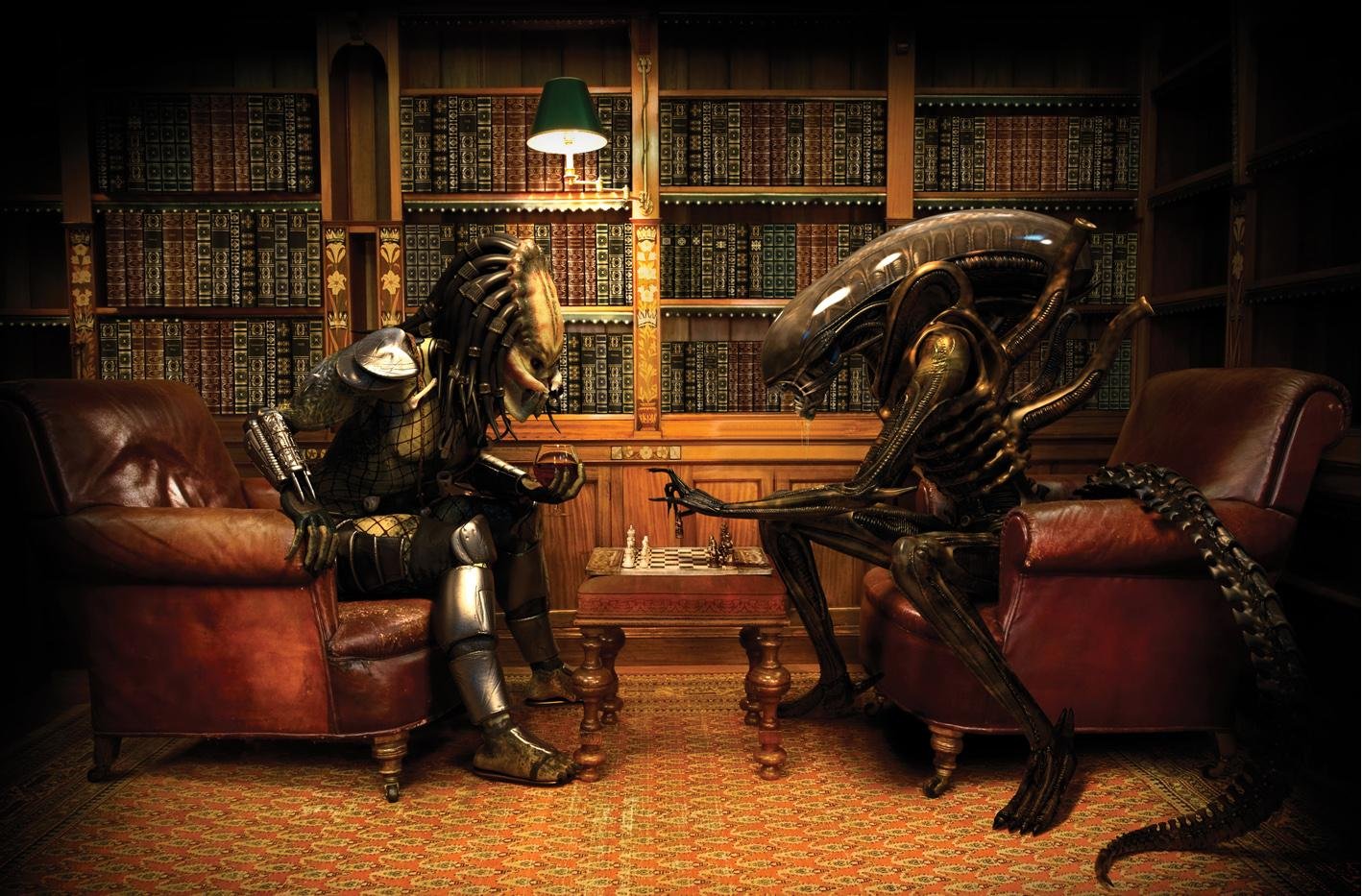

Who will win the compulsory licensing war – 'Alien' bigpharma or generic 'Predators'

When Indian patent office granted compulsory license to Hyderabad-based Natco Pharma to market a generic version of a patented cancer treatment Nexavar in March this year, eyebrows were raised around the world. Another case that is being closely followed by national and international media is Novartis' Glivec case where the multinational pharmaceutical giant is fighting for a patent based on increased safety of the drug due to modification of the naked chemical molecule. In another development, the Delhi patent office revoked a patent to Pfizer for its kidney cancer drug Sutent (sunitinib) following post-grant opposition by major generics players Cipla and Natco Pharma.

The debate is still on whether the Indian patent scenario is favorable for research and development of new drugs given the recent developments, but experts agree that compulsory licensing needs prudent use.

Mr Kirit S Javali, partner, Jafa & Javali, Advocates, New Delhi, elaborates that the grant of a patent confers limited monopoly on the patentee to the exclusion of others. "Though the law permits this, it also takes into account the fact that the monopoly granted through a patent may be abused and, hence, provides for certain restrictions to its enjoyment. The grant of compulsory license is one such restriction imposed on the absolute exploitation of a patent," he says.

Mr Y H Gharpure, Gharpure Consulting Engineers, Pune, says, "There is a provision in the patent act for government to evoke compulsory licensing under clause 100 as has been done by Brazil, thereby forcing the multinationals either to reduce the exorbitant prices of the patented drugs or the government take recourse to compulsory licensing and give the same to several companies so that essential drugs are available at reasonable prices."

India is not the first nation to have granted compulsory license to a drug company for a patent product. In last 10 years, governments of developing nations such as Zimbabwe (2003), Malaysia (2003), Zambia (2004), Indonesia (2004 and 2007), Thailand (2006 and 2007) and Brazil (2007) have evoked compulsory licensing to increase patients' access to medicines. But even after six months after the verdict on compulsory license to Natco Pharma for Nexavar, the debate is still raging on whether it was the right move.

India amended its Patents Act in 2005. "(Provision of ) Compulsory license was in place even before that, but it was never used," points out Mr K V Balasubramanian, managing director, Indian Immunologicals, Hyderabad. "For any society where people are unable to meet their daily requirements, compulsory licensing will bring in cheer as the healthcare costs are beyond their reach. India granted its first ever compulsory license to Natco Pharma only this year. Thailand and many developing nations have already granted compulsory licensing to overcome the monopoly in the market. If I am not wrong, even developed nation such as Canada has used compulsory licensing earlier."

Dr Ajay Kumar Sharma, associate director - Pharma & Biotech, Healthcare Practice, Frost & Sullivan, South Asia & Middle East, calls compulsory licensing "a double edged sword". "It helps the patented products to become more affordable and accessible in order to save lives, thus helping the society at large. But if one has to analyze, in the long run it deprives the innovator companies from making money, which they would have invested in discovering this successful drug and many unsuccessful trials. Also this money helps them to generate a surplus amount for funding future research, which can be of immense use to mankind to fight newer disease challenges."

Dr Sharma says by "awarding compulsory licenses (on impulse), we are destroying this natural market equilibrium". "Hence, the best way in such case would be that the government chips in by providing these essential medicines at subsidized rates to people rather than destroying the market equilibrium under the guise of compulsory licensing," he adds.

Ms Sunita K Sreedharan, partner, SKS Law Associates, New Delhi, points out that in areas such as healthcare "patented inventions appear to evoke high emotional content". "In case of epidemics, the Patents Act provides for government intervention. In a routine system, the Drug Price Control Order can be used to control prices without resorting to the grant of compulsory licensing. Similarly, companies holding the patent can be encouraged to make the patented drugs available to the afflicted patients belonging to the poorer sections of the society through corporate social responsibility programs to be implemented with a certain time period failing which the compulsory licensing can be granted," she says.

Echoing similar sentiments, Mr K V Balasubramanian of Indian Immunologicals, says the governing agency should issue compulsory licensing after proper examination and considering many aspects such as need, urgency and affordability. "Otherwise, decisions based on only technical aspects will open up the matter for a debate. A core committee comprising the Ministry of Health and scientists from different backgrounds should take the decision based upon situations and need instead of the patent office judging the case purely on technical matters. Then only it will serve the purpose of granting compulsory license to improve access of essential medicines," he says.

Ms Sunita K Sreedharan concludes that the society must not lose sight of the fact that the patent system is a mere tool that can be used effectively to benefit society by bringing in technological progress or to its detriment by blocking development of technology. "And in the latter context, it is important to identify and block entities that use compulsory licensing as a tool for a low-cost piggy-back ride on an R&D company to attain bigger profits with least scientific or business efforts," she says.

Why compulsory licensing?

In India, the provisions on compulsory licensing was introduced into the Patents Act pursuant to the recommendations by the Ayyangar Committee. The predominant purpose behind the grant of a compulsory license is to ensure the supply of the patented invention in the Indian market. Patents are not granted to enable the patentee to enjoy a monopoly by importing the patented articles into India.

"The Patents Act makes the working of the invention in India an important requirement. At the same time, the effort expended by the patentee in inventing the patented article, the expenditure incurred in research and development, and in obtaining and keeping the patent in force cannot be disregarded. The provisions on compulsory licensing endeavors to secure that the articles manufactured under the patent shall be available to the public at the lowest prices consistent with the patentees deriving a reasonable advantage from their patent rights," says Mr Kirit S Javali, partner, Jafa & Javali, Advocates, New Delhi.

"As the patent regime came in full force under World Trade Organization (WTO) from 2005, the MNCs started registering patents for a large number of new drugs, importing the products and marketing them in India without working the patent," says Mr Y H Gharpure of Gharpure Consulting Engineers, who has been studying the compulsory licensing issue. "If the patent is not working for three years, the compulsory licensing provision can be evoked as was done by Natco Pharma. There is a case for evoking such provisions for many other patented products for treatment of cancer, HIV/AIDs, etc. This, however, will become apparent if the information patentee files to the patent authorities under form 27 is made public. This will clearly reveal whether the patent is being worked in India or otherwise. Currently, although the information is available on request, it is not available in public domain."

WHO supports measures that improve access to essential medicines (Source:www.moph.go.th)

A report, Improving access to medicines in Thailand: The use of TRIPS flexibilities, prepared by a team of seven experts from WHO, UNDP, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development and WHO South East Asia Regional Office made the following four remarks after visiting Bangkok in 2008 and holding discussions with stakeholders aimed at facilitating an understanding of the context and circumstances related to the granting of compulsory licenses in Thailand. The following are the remarks:

In seeking greater access to essential medicines, national authorities may consider the full range of mechanisms available to contain costs of essential medicines and examine how the various tools may complement one another.

A sustainable system for the funding of medicines could be based on three main components: 1) the creation or enhancement of a national/social health insurance or of medicine prepayment mechanisms; 2) the introduction and use of all possible cost- containment mechanisms, and 3) the use of TRIPS-compliant flexibilities. The TRIPS Agreement contains a range of mechanisms and options to protect public health that countries can consider when formulating intellectual property laws and public health policies.

The use of compulsory licence and government use provisions to improve access to medicines is one of the several cost-containment mechanisms that may be used for patented essential medicines not affordable to the people or to public health insurance schemes. WHO supports measures which improve access to essential medicines, including application of TRIPS flexibilities.